The Scandinavians lived in and colonized places so far north that the time measuring conventions of continental Europe were inadequate. Not only were the days of winter so much shorter than they were further south, the sun barely rose above the horizon, with a track that arched only slightly higher at noon than it did during the rest of the day.

The Scandinavians lived in and colonized places so far north that the time measuring conventions of continental Europe were inadequate. Not only were the days of winter so much shorter than they were further south, the sun barely rose above the horizon, with a track that arched only slightly higher at noon than it did during the rest of the day.

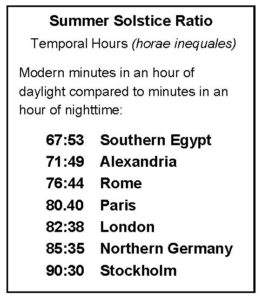

In the rest of Europe, the day was divided into 12 hours of daylight and 12 hours of nighttime. The length of these “hours” varied depending on the time of year. Only on the equinoxes was an hour of daylight 60 minutes long. In other words, on the summer solstice, in Rome an hour of daylight was 76 minutes long using our modern measurements, and an hour of nighttime was 44 minutes long.

The further north you travel, the longer each hour of daylight becomes. By dividing the hours of daylight into 12 unequal hours, on the summer solstice you end up with a ratio 80 minutes per hour of daylight to 40 minutes per hour of nighttime in Paris, 85 minutes of daylight to 35 minutes of nighttime in northern Germany, 90 minutes of daylight to 30 minutes of nighttime in Stockholm, and 105 minutes of daylight to 15 minutes of nighttime in Reykjavik, Iceland. The reverse was true in the winter, when a daytime hour would measure 30 minutes long in Stockholm and only 15 minutes long in Reykjavik. Clearly the 12-hour convention of southern Europe works poorly in lands nearing the Arctic Circle.

Instead the Scandinavians divided the day into eight equal parts. In the winter the sun would still be below the horizon for much of the day, but “daymarks” (dagmarks) could be measured even during the shortest days of the year. That’s because daymarks relied on the direction of the sun. The Scandinavian system divided the horizon into eight sections by direction (north, northeast, east, southeast, south, southwest, west and northwest).

Instead the Scandinavians divided the day into eight equal parts. In the winter the sun would still be below the horizon for much of the day, but “daymarks” (dagmarks) could be measured even during the shortest days of the year. That’s because daymarks relied on the direction of the sun. The Scandinavian system divided the horizon into eight sections by direction (north, northeast, east, southeast, south, southwest, west and northwest).

Of course the most important daymark each day was noon, when the sun was at its zenith. Known as “Highday” or “Midday” (hádegi or middag), it was the mid-point in the sun’s path across the sky. Unlike the geographic locations of sunrise and sunset, which moved significantly during the year, at midday the sun was in the same place every day.

Equinoctal View of the South Horizon from a Scandinavian Farm

Most Scandinavians used a landmark to identify midday, or highday. There are numerous mountains in Norway named Middagsfjället, Middagshorn and Middagsberg, for example, and in Iceland, Hádegisbrekkur (for highday). Other geographic features used to mark midday were mountain passes, bridges, and fields.

Opposite midday was midnight (miðnætti). In latitudes approaching the Arctic Circle it is easy to establish a landmark for midnight by watching the horizon during June. Although the sun has set before midnight, it is so close to the horizon that the twilight is often bright enough to note where the sun is beneath the horizon. When the sun reaches its lowest point, it is midnight. And of course, at midnight the sun is due north, just as it is due South at noon.

Summer View of the North Horizon from a Scandinavian Farm

Half-way between midnight and midday was mid-morning or rise-measure. This is when the sun is due east. On the equinoxes the sun would rise at this point on the horizon. During the summer the sun would rise long before the nighttime sleep period was over, and during the winter people would wake up long before the sun rose. The sun would rise closer to the midnight marker in the summer and closer to the midday marker in the winter, but the geographic marker for mid-morning would be some feature due east, such as a tree, a valley or another mountain peak. Likewise the point half-way between noon and midnight, mid-evening, was located due west.

Winter View of the South Horizon from a Scandinavian Farm

In between these four cardinal points of the compass were four more geographic markers for times of the day. Between midnight and mid-morning was ótta, roughly 3 am, and between mid-morning and midday was day-measure, about 9 am. After noon was undorn, about 3 pm. And at about 9 pm is night-measure. In all eight directions are used to tell the time, a system that makes sense when the sun is in the sky for wildly different amounts of time during the year. The system uses the location of the sun, whether the sun can be seen above the horizon or not, to tell time.

Summer View of the South Horizon from a Scandinavian Farm

In Anglo-Saxon England during the Viking era, they used a system similar to that of the Scandinavians in that there were eight “tides” to the day. But contact with the Roman Catholic Church and European culture in general led to differences between the English tides and the Scandinavian átts. The English tides don’t seem to be tied to a geographic direction the way the Scandinavian time-telling system was.

For more information on this topic, check out the web page “Telling Time Without a Clock: Scandinavian Daymarks” written for teachers by staffers at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. The page is at http://hea-www.harvard.edu/ECT/Daymarks/#3back. Another good online source is “Time and Travel in Old Norse Society,” a paper published by Thorsteinn Vilhjalmsson of the Science Institute, University of Iceland.

You must be logged in to post a comment.