This paper by Richard Fitch of the Historic Royal Palaces discusses the difficulties of recreating Medieval material culture, and some of the gotchas to watch out for

This paper by Richard Fitch of the Historic Royal Palaces discusses the difficulties of recreating Medieval material culture, and some of the gotchas to watch out for

How did our medieval English counterparts really sound? Would we have been able to understand them?

How did our medieval English counterparts really sound? Would we have been able to understand them?

An app developed by a team at the University of Saskatchewan, Canada, with the help and encouragement of medieval scholar and Monty Python alum Terry Jones, has made it possible to hear and see the General Prologue of the Canterbury Tales on your phone, tablet or computer.

The free app is available from iPhone’s app store, Google Play and at http://www.sd-editions.com/CantApp/GP/.

The app allows you to hear Chaucer’s words as they would have sounded in his day while the prologue is displayed in both Middle English and modern English. The app displays one or two lines at a time, advancing as the narration proceeds. It’s a fascinating way to learn more about Chaucer and Middle English. You can also see the full prologue in either Middle English or its modern translation.

You also can just listen to the narration like a podcast, but without the modern translation to guide you, it can be a bit difficult to understand. If you want to listen to the Canterbury Tales in modern English, you can find downloadable audiobooks and audiobook CDs at most libraries.

If you’re not interested in the text or you don’t want to download another app, you can see the 2015 performance of the prologue at https://artsandscience.usask.ca/english/research/performances/the-general-prologue-in-historically-based-performance.php.

This was one of the last things Terry Jones worked on before he died earlier this year, and the team dedicated the app to him.

Peter Robinson of the University of Saskatchewan described to Open Culture how Jones’ behind-the-scenes influence helped drive this project. “‘His work and his passion for Chaucer was an inspiration for us. We talked a lot about Chaucer and it was his idea that the Tales would be turned into a performance.'”

The Open Culture website noted that “The strangeness of Middle English to our eyes and ears can make approaching the Canterbury Tales for the first time a daunting experience. The Chaucer app is an excellent research tool for scholars, yet the researchers want ‘the public, not just academics to see the manuscript as Chaucer would have likely thought of it,’ says Robinson, ‘as a performance that mixed drama and humor.’ In other words, reading Chaucer should be fun.

“Why else would Terry Jones—a man who knew his comedy as well as his medieval history—spend decades reading and writing about him?”*

*”Terry Jones, the Late Monty Python Actor, Helped Turn Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales Into a Free App: Explore It Online,” Open Culture, http://www.openculture.com/2020/02/terry-jones-the-late-monty-python-actor-helped-turn-chaucers-canterbury-tales-into-a-free-app.html, retrieved April 25, 2020.

A recent email from Academia.edu recommended the paper The Representation of Lordship and Land Tenure in Domesday Book by Stephen Baxter, faculty member in the Department of History at the University of Oxford. The paper is embedded below.

I encourage anyone interested in late Anglo-Saxon and early Conquest England to check out his papers at:

https://oxford.academia.edu/StephenBaxter

The basic membership at Academia.edu is free, and there are a wealth of papers and articles

Article from Academia.edu, compiled by Dr. Richard Abels of the US Naval Academy.

Interesting timeline/chronology with hyperlinks “to primary sources in translation or to contemporary illustrations”

This came to my notice from Academia.edu.

The introduction explains the data, the Excel spreadsheet contains the records as they have been translated.

The Scandinavians lived in and colonized places so far north that the time measuring conventions of continental Europe were inadequate. Not only were the days of winter so much shorter than they were further south, the sun barely rose above the horizon, with a track that arched only slightly higher at noon than it did during the rest of the day.

The Scandinavians lived in and colonized places so far north that the time measuring conventions of continental Europe were inadequate. Not only were the days of winter so much shorter than they were further south, the sun barely rose above the horizon, with a track that arched only slightly higher at noon than it did during the rest of the day.

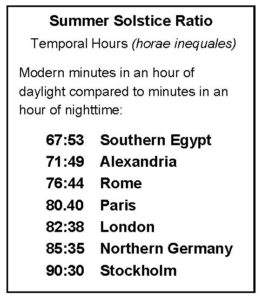

In the rest of Europe, the day was divided into 12 hours of daylight and 12 hours of nighttime. The length of these “hours” varied depending on the time of year. Only on the equinoxes was an hour of daylight 60 minutes long. In other words, on the summer solstice, in Rome an hour of daylight was 76 minutes long using our modern measurements, and an hour of nighttime was 44 minutes long.

The further north you travel, the longer each hour of daylight becomes. By dividing the hours of daylight into 12 unequal hours, on the summer solstice you end up with a ratio 80 minutes per hour of daylight to 40 minutes per hour of nighttime in Paris, 85 minutes of daylight to 35 minutes of nighttime in northern Germany, 90 minutes of daylight to 30 minutes of nighttime in Stockholm, and 105 minutes of daylight to 15 minutes of nighttime in Reykjavik, Iceland. The reverse was true in the winter, when a daytime hour would measure 30 minutes long in Stockholm and only 15 minutes long in Reykjavik. Clearly the 12-hour convention of southern Europe works poorly in lands nearing the Arctic Circle.

Instead the Scandinavians divided the day into eight equal parts. In the winter the sun would still be below the horizon for much of the day, but “daymarks” (dagmarks) could be measured even during the shortest days of the year. That’s because daymarks relied on the direction of the sun. The Scandinavian system divided the horizon into eight sections by direction (north, northeast, east, southeast, south, southwest, west and northwest).

Instead the Scandinavians divided the day into eight equal parts. In the winter the sun would still be below the horizon for much of the day, but “daymarks” (dagmarks) could be measured even during the shortest days of the year. That’s because daymarks relied on the direction of the sun. The Scandinavian system divided the horizon into eight sections by direction (north, northeast, east, southeast, south, southwest, west and northwest).

Of course the most important daymark each day was noon, when the sun was at its zenith. Known as “Highday” or “Midday” (hádegi or middag), it was the mid-point in the sun’s path across the sky. Unlike the geographic locations of sunrise and sunset, which moved significantly during the year, at midday the sun was in the same place every day.

Equinoctal View of the South Horizon from a Scandinavian Farm

Most Scandinavians used a landmark to identify midday, or highday. There are numerous mountains in Norway named Middagsfjället, Middagshorn and Middagsberg, for example, and in Iceland, Hádegisbrekkur (for highday). Other geographic features used to mark midday were mountain passes, bridges, and fields.

Opposite midday was midnight (miðnætti). In latitudes approaching the Arctic Circle it is easy to establish a landmark for midnight by watching the horizon during June. Although the sun has set before midnight, it is so close to the horizon that the twilight is often bright enough to note where the sun is beneath the horizon. When the sun reaches its lowest point, it is midnight. And of course, at midnight the sun is due north, just as it is due South at noon.

Summer View of the North Horizon from a Scandinavian Farm

Half-way between midnight and midday was mid-morning or rise-measure. This is when the sun is due east. On the equinoxes the sun would rise at this point on the horizon. During the summer the sun would rise long before the nighttime sleep period was over, and during the winter people would wake up long before the sun rose. The sun would rise closer to the midnight marker in the summer and closer to the midday marker in the winter, but the geographic marker for mid-morning would be some feature due east, such as a tree, a valley or another mountain peak. Likewise the point half-way between noon and midnight, mid-evening, was located due west.

Winter View of the South Horizon from a Scandinavian Farm

In between these four cardinal points of the compass were four more geographic markers for times of the day. Between midnight and mid-morning was ótta, roughly 3 am, and between mid-morning and midday was day-measure, about 9 am. After noon was undorn, about 3 pm. And at about 9 pm is night-measure. In all eight directions are used to tell the time, a system that makes sense when the sun is in the sky for wildly different amounts of time during the year. The system uses the location of the sun, whether the sun can be seen above the horizon or not, to tell time.

Summer View of the South Horizon from a Scandinavian Farm

In Anglo-Saxon England during the Viking era, they used a system similar to that of the Scandinavians in that there were eight “tides” to the day. But contact with the Roman Catholic Church and European culture in general led to differences between the English tides and the Scandinavian átts. The English tides don’t seem to be tied to a geographic direction the way the Scandinavian time-telling system was.

For more information on this topic, check out the web page “Telling Time Without a Clock: Scandinavian Daymarks” written for teachers by staffers at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. The page is at http://hea-www.harvard.edu/ECT/Daymarks/#3back. Another good online source is “Time and Travel in Old Norse Society,” a paper published by Thorsteinn Vilhjalmsson of the Science Institute, University of Iceland.

Master Crag Duggan approached me a few months ago about creating an online repository for his historical material; a collection of interviews and stories he made and collected as he researched and documented the early history of Calontir. After discussing with Crag and with Mistress Sofya la Rus, we determined that the Calontiri Wiki would be the best platform.

Master Crag Duggan approached me a few months ago about creating an online repository for his historical material; a collection of interviews and stories he made and collected as he researched and documented the early history of Calontir. After discussing with Crag and with Mistress Sofya la Rus, we determined that the Calontiri Wiki would be the best platform.

Sofya has completed uploading the first tranche of material, and it is available now at Category:Master Crag’s Histories

We hope you enjoy them.

Mathurin

Non Nobis Solum

Adoration of the Magi by Bartolomé Esteban Murillo

As it grew dark on Christmas Eve and people filed into church for the Vespers service, the late afternoon/evening service now held around 4 pm, the Christmas season officially began for medieval folk, at least for those in the Christian West.

Unlike us, who begin our Christmas season before the holiday, at Thanksgiving or even earlier, our medieval counterparts began the season with the religious events surrounding Christmas Eve and Christmas Day. Decorations were put up right before Christmas, often on Christmas Eve. I imagine our medieval alter-egos would have frowned on the concept of decorating to celebrate the birth of Jesus before Advent even began.

We live in a secular country that notes holidays like Ramadan and Yom Kippur on its calendars. It’s hard to truly comprehend how much religion and the Christian liturgical calendar were part of everyday medieval life. For the common folk the liturgical calendar was more important than the Julian calendar. Letters were dated by the holy day or week, for example “written on St. Catherine’s Day” or “on the Saturday before Ash Wednesday.” Few used the complicated Roman calendar to date personal correspondence (“vij kalendas Februarias”). Everyone knew when Holy Rood Day or Michaelmas was.

The first day of Christmastide, December 25, was followed by the second day, the Feast of St. Stephen, then the third day, the feast of St. John the Evangelist, and so on. On the evening before the twelfth day of Christmas, January 5, the celebration of Epiphanytide began. The Feast of the Epiphany, which celebrated the visit of the three wise men, or three kings, to the baby Jesus, also celebrated the baptism of Christ during SCA period and to a lesser extent, the miracle at the wedding at Cana. It ended eight days later, on January 13.

Christmas, Epiphany, Lady Day, All Saints’ Day, the feasts of the Ascension of Christ and the Assumption of the Virgin Mary are some of the most important Church holy days, known as Solemnity Days. These days outrank regular saints’ days and memorials. The celebration of Solemnity Days always began the day before, at Vespers.

All these Christian holy days, which is, of course, where our word holiday comes from, were part of the liturgical calendar for the year. Some, like Christmas, were fixed dates. Others, like the first Sunday of Advent, were moveable dates that were computed from when another Church holiday fell on the calendar. Easter, that most complicated Church holiday, determined when many of the other church events took place. I suspect that most people didn’t worry about computing each year’s calendar and simply let their churchmen tell them when to feast and when to fast.

When exactly did Christmas end? Christmastide ended on Twelfth Night. Shakespeare mentions people taking down the Christmas decorations on Twelfth Night. If you include Epiphanytide, you extend the holiday season another week. But in some places they remove Christmas decorations on Candlemas Eve (Feb. 1), and some calendars describe Feb. 1 as the end of the Christmas season. Christians believe February 2 is when Jesus was presented in the Temple and when Mary was purified, so continuing the season of the birth of Jesus until February 2 has some logic to it. However, it seems to be more of a post-SCA period practice.

So what happened after Epiphanytide? The weeks between major Church events were known as Ordinary Time. These weeks were numbered, from one to 34, and usually began the Monday after a significant church time period. For example, Ordinary Time begins on January 14, the day after the end of Epiphanytide, with the first Sunday of Ordinary Time on January 20 this year.

Below is part of a reconstructed medieval liturgical calendar. Since my persona is 12th century English, it represents the holidays and saints’ days my persona would have known.[i] It covers the time from the birth of Jesus to his presentation in the Temple.

Reconstructed Medieval Liturgical Year

Constructed Using 2018-2019 as the Example

Dates marked with (M) are moveable feasts or days of worship. Dates in bold are Solemnity feasts[ii], Church events deemed more important than regular feast days. Optional or obligatory memorial observances are in italic.

| Christmastide (beginning of a week off for the peasantry) | |||

| Christmas/Feast of the Nativity of Jesus Christ | Dec. 25, 2018 | ||

| Feast of St. Stephen | Dec. 26 | ||

| Feast of St. John the Evangelist | Dec. 27 | ||

| Childermas (Feast of the Holy Innocents) | Dec. 28 | ||

| St. Thomas Becket (from 12th century) | Dec. 29 | ||

| Feast of the Circumcision (eight Roman days after Christmas) | Jan. 1, 2019 | ||

| Twelfth Night (eve of the 12th day of Christmas/end of Christmas) | Jan. 5 | ||

| Epiphanytide[iii] | |||

| Feast of the Epiphany (Visit of the Magi/Baptism of Christ) | Jan. 6 | ||

| End of Epiphanytide | Jan. 13 | ||

| Ordinary Time (ordinal – the counted weeks)[iv] | Jan. 14 | ||

| (Begins on January 14 this year) | |||

| First Sunday of Ordinary Time | Jan. 20 | ||

| Second Sunday of Ordinary Time | Jan. 27 | ||

| Candlemas/Feast of the Presentation of Christ/Feast of the Purification of the Virgin | Feb. 2 | ||

[i] Modern liturgical calendars have additional holy days or have removed or added saints’ days. For example, the celebration of the baptism of Jesus is now held on the Sunday after Epiphany in the Roman Catholic Church.

[ii] Solemnities replace Sunday services when they fall on a Sunday. Celebration of Solemnity feasts begins the night before at Vespers.

[iii] Modern church calendars consider Epiphanytide a subset, or part of, Christmastide.

[iv] Ordinary Time runs from the Monday after the Sunday that follows Epiphany (January 13 this year) to the Tuesday before Ash Wednesday (March 5 this year), then resumes on the Monday after Pentecost Sunday (June 10 this year) and concludes before First Vespers of the First Sunday of Advent (Dec. 1 in 2018).

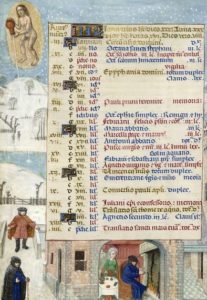

January from a Book of Hours (British Library)

Tonight at midnight most of the world will celebrate the new year. But few of our medieval counterparts used January 1 as the start of the new year. When your persona marked the change of the year depended on where you lived, and when.

Are you French, Italian, German, English, Byzantine? Each of these places celebrated the new year on a different date.

At least seven different calendar styles were used in the Christian West alone. And to make matters worse, some areas (Spain in particular) would use one convention for several centuries, change to another, then change to yet another style a few hundred years later.

Depending on when and where you lived in SCA period, New Year’s Day could be:

January 1: Circumcision Style – extends from Jan. 1 to Dec. 31. Named for the Feast of the Circumcision (eight Roman days after Jesus’s birth), this style, which is nearly universal now, was perhaps the least used style. Julius Caesar imposed this change on the Roman world with his new calendar in 46 BC, and many others have tried to implement it at different times during SCA period. William the Conqueror made January 1 the beginning of the new year in England, but the people used March 25 for most purposes.

March 1: Venetian Style – from March 1 of the given year (2019) to the last day of February of the subsequent year 2020). Derived from the pre-Caesarian Roman style, it was used by the Merovingian Franks and was the official style in Venice until 1797. So for the Venetians, the new year will not begin for three months.

March 25: Annunciation Style – begins the year on March 25 of the previous year (stilus pisanus 2020) or on March 25 of the given year (stilus florentinus, mos anglicanus 2019). This was one of the most popular styles during the Middle Ages. In England, March 25, or Lady Day, still marked the beginning of the new year for a variety of purposes.

Although they used the Annunciation Style in Pisa, they started counting a year earlier than everyone else. In other words, the new year might begin on March 25 in both Pisa and Florence, but in Piza it already would be 2019, and would become 2020 in March, while in Florence it would still be 2018 until March 25, when it would become 2019.

Easter Style – Begins the year on the movable feast of Easter Sunday of the given year. Sometimes the year is too short, and other times too long. This year would run from Easter Sunday, April 21, 2019 to Holy Saturday, April 11, 2020. Because Easter can fall on a day somewhere between March 22 and April 25, there is a possibility a date could occur twice in one year. The two dates had to be distinguished by marking them “after Easter” and “before Easter.” This style was the most popular one in France.

September 1: Byzantine Style – extends from September 1 of the previous year (2018) to August 31 of the given year (2019), in accordance with the Byzantine use of dating from the creation of the world.

This style was used by areas influenced by Constantinople, particularly during early period. Since Justinian’s time it was the day taxes were due.

September 24: Indictio Bedana – extends from September 24 of the previous year (2018) to September 23 of the given year (2019). Introduced by England’s “Venerable” Bede during the late 8th century, it was never used in that country, although later it was widely used on the Continent, especially in Germany and by the Imperial chancellery. It uses a date near the fall equinox, rather than the spring equinox, for the beginning of the year.

December 25: Christmas Style – extends from December 25 of the previous year (2018) to December 24 of the given year (2019). This is the style most widely used in the Middle Ages. It is the style that held sway during Anglo-Saxon England’s era, as well as being the New Year of choice for parts of France and Spain for 200 years.

Completely confused? You’re not alone. Historian Reginald Poole gave the following example:

“If we suppose a traveler to set out from Venice on March 1, 1245, the first day of the Venetian year, he would find himself in 1244 when he reached Florence; and if after a short stay he went on to Pisa, the year 1246 would already have begun there. Continuing his journey westward, he would find himself again in 1245 when he entered Provence, and on arriving in France before Easter (April 21) he would be once more in 1244. This seems a bewildering tangle of dates.”

The easiest way to determine how your persona would have dated the year is to use the online Calendar Utility created and maintained by Dr. Otfried Lieberknecht at: http://www.lieberknecht.de/~prg/calendar.htm. This is an amazingly useful tool. You can type in a Roman-style date and find out what its modern-style calendar date is. You can plug in any date and see what its official Roman calendar date is, along with what year it would be. For example, today is ii Kalendas (or Primus Kalendas) Januarius (the day before the Kalends of January) 2018 for me, because my persona is 12th century English. My new year is nearly four months away.

For those with non-Christian or early period personas, the task of identifying New Year’s Day can be challenging. In non-Christian parts of Europe, such as Scandinavia, parts of Germany and eastern Europe, local pagan customs prevailed. Most celebrated the new year sometime in March, usually tied to a spring fertility festival, although customs vary widely.

For those with Muslim personas or with personas that lived in Islamic-ruled areas of Spain or Sicily, tying the Muslim New Year to a Christian calendar date can be a challenge. Because the Muslims use a strictly lunar calendar, the Islamic year is only 354 days long. The Islamic new year begins eleven days earlier each year. It changes months and seasons regularly. Perhaps someone with a Muslim persona knows of a similar calendar utility to figure out historical dates. If so, please share.

And while Jewish personas would, of course, celebrate Rosh Hashanah in September, they most likely would keep secular records the same way others in their area did.

So to all of you, Happy New Year – sometime this year.

Unto the populace of Calontir, on behalf of Their Highnesses, I, Count Marius Lucian Fidelis, send word.

At the Coronation feast to be held III days before the Ides of Janus (January 12, 2019) there will be a game of wit and memory.

Some might call the ability to remember places and dates Trivial! I say having a strong grasp of history prepares us for the future.

Form your teams, purchase your feast tickets. And while we feast we will test our knowledge of the history, both mundane and societal.

The game will consist of 2 rounds of 10 questions, for best advantage build your teams with a broad range of mundane and society knowledge.

The ability to pre-purchase feast tickets is forthcoming. In the mean time, assemble your teams and be prepared to purchase tickets at gate.

You must be logged in to post a comment.