A short survey article of pottery making finds in Northumberland, from prehistory to modern times, including some experimental re-creation. By Richard Carlton. From Academia.edu.

Arts & Sciences

Twelfth Night, Christmastide and Epiphanytide

Adoration of the Magi by Bartolomé Esteban Murillo

As it grew dark on Christmas Eve and people filed into church for the Vespers service, the late afternoon/evening service now held around 4 pm, the Christmas season officially began for medieval folk, at least for those in the Christian West.

Unlike us, who begin our Christmas season before the holiday, at Thanksgiving or even earlier, our medieval counterparts began the season with the religious events surrounding Christmas Eve and Christmas Day. Decorations were put up right before Christmas, often on Christmas Eve. I imagine our medieval alter-egos would have frowned on the concept of decorating to celebrate the birth of Jesus before Advent even began.

We live in a secular country that notes holidays like Ramadan and Yom Kippur on its calendars. It’s hard to truly comprehend how much religion and the Christian liturgical calendar were part of everyday medieval life. For the common folk the liturgical calendar was more important than the Julian calendar. Letters were dated by the holy day or week, for example “written on St. Catherine’s Day” or “on the Saturday before Ash Wednesday.” Few used the complicated Roman calendar to date personal correspondence (“vij kalendas Februarias”). Everyone knew when Holy Rood Day or Michaelmas was.

The first day of Christmastide, December 25, was followed by the second day, the Feast of St. Stephen, then the third day, the feast of St. John the Evangelist, and so on. On the evening before the twelfth day of Christmas, January 5, the celebration of Epiphanytide began. The Feast of the Epiphany, which celebrated the visit of the three wise men, or three kings, to the baby Jesus, also celebrated the baptism of Christ during SCA period and to a lesser extent, the miracle at the wedding at Cana. It ended eight days later, on January 13.

Christmas, Epiphany, Lady Day, All Saints’ Day, the feasts of the Ascension of Christ and the Assumption of the Virgin Mary are some of the most important Church holy days, known as Solemnity Days. These days outrank regular saints’ days and memorials. The celebration of Solemnity Days always began the day before, at Vespers.

All these Christian holy days, which is, of course, where our word holiday comes from, were part of the liturgical calendar for the year. Some, like Christmas, were fixed dates. Others, like the first Sunday of Advent, were moveable dates that were computed from when another Church holiday fell on the calendar. Easter, that most complicated Church holiday, determined when many of the other church events took place. I suspect that most people didn’t worry about computing each year’s calendar and simply let their churchmen tell them when to feast and when to fast.

When exactly did Christmas end? Christmastide ended on Twelfth Night. Shakespeare mentions people taking down the Christmas decorations on Twelfth Night. If you include Epiphanytide, you extend the holiday season another week. But in some places they remove Christmas decorations on Candlemas Eve (Feb. 1), and some calendars describe Feb. 1 as the end of the Christmas season. Christians believe February 2 is when Jesus was presented in the Temple and when Mary was purified, so continuing the season of the birth of Jesus until February 2 has some logic to it. However, it seems to be more of a post-SCA period practice.

So what happened after Epiphanytide? The weeks between major Church events were known as Ordinary Time. These weeks were numbered, from one to 34, and usually began the Monday after a significant church time period. For example, Ordinary Time begins on January 14, the day after the end of Epiphanytide, with the first Sunday of Ordinary Time on January 20 this year.

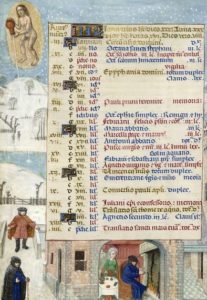

Below is part of a reconstructed medieval liturgical calendar. Since my persona is 12th century English, it represents the holidays and saints’ days my persona would have known.[i] It covers the time from the birth of Jesus to his presentation in the Temple.

Reconstructed Medieval Liturgical Year

Constructed Using 2018-2019 as the Example

Dates marked with (M) are moveable feasts or days of worship. Dates in bold are Solemnity feasts[ii], Church events deemed more important than regular feast days. Optional or obligatory memorial observances are in italic.

| Christmastide (beginning of a week off for the peasantry) | |||

| Christmas/Feast of the Nativity of Jesus Christ | Dec. 25, 2018 | ||

| Feast of St. Stephen | Dec. 26 | ||

| Feast of St. John the Evangelist | Dec. 27 | ||

| Childermas (Feast of the Holy Innocents) | Dec. 28 | ||

| St. Thomas Becket (from 12th century) | Dec. 29 | ||

| Feast of the Circumcision (eight Roman days after Christmas) | Jan. 1, 2019 | ||

| Twelfth Night (eve of the 12th day of Christmas/end of Christmas) | Jan. 5 | ||

| Epiphanytide[iii] | |||

| Feast of the Epiphany (Visit of the Magi/Baptism of Christ) | Jan. 6 | ||

| End of Epiphanytide | Jan. 13 | ||

| Ordinary Time (ordinal – the counted weeks)[iv] | Jan. 14 | ||

| (Begins on January 14 this year) | |||

| First Sunday of Ordinary Time | Jan. 20 | ||

| Second Sunday of Ordinary Time | Jan. 27 | ||

| Candlemas/Feast of the Presentation of Christ/Feast of the Purification of the Virgin | Feb. 2 | ||

[i] Modern liturgical calendars have additional holy days or have removed or added saints’ days. For example, the celebration of the baptism of Jesus is now held on the Sunday after Epiphany in the Roman Catholic Church.

[ii] Solemnities replace Sunday services when they fall on a Sunday. Celebration of Solemnity feasts begins the night before at Vespers.

[iii] Modern church calendars consider Epiphanytide a subset, or part of, Christmastide.

[iv] Ordinary Time runs from the Monday after the Sunday that follows Epiphany (January 13 this year) to the Tuesday before Ash Wednesday (March 5 this year), then resumes on the Monday after Pentecost Sunday (June 10 this year) and concludes before First Vespers of the First Sunday of Advent (Dec. 1 in 2018).

Is It New Year’s Day?

January from a Book of Hours (British Library)

Tonight at midnight most of the world will celebrate the new year. But few of our medieval counterparts used January 1 as the start of the new year. When your persona marked the change of the year depended on where you lived, and when.

Are you French, Italian, German, English, Byzantine? Each of these places celebrated the new year on a different date.

At least seven different calendar styles were used in the Christian West alone. And to make matters worse, some areas (Spain in particular) would use one convention for several centuries, change to another, then change to yet another style a few hundred years later.

Depending on when and where you lived in SCA period, New Year’s Day could be:

January 1: Circumcision Style – extends from Jan. 1 to Dec. 31. Named for the Feast of the Circumcision (eight Roman days after Jesus’s birth), this style, which is nearly universal now, was perhaps the least used style. Julius Caesar imposed this change on the Roman world with his new calendar in 46 BC, and many others have tried to implement it at different times during SCA period. William the Conqueror made January 1 the beginning of the new year in England, but the people used March 25 for most purposes.

March 1: Venetian Style – from March 1 of the given year (2019) to the last day of February of the subsequent year 2020). Derived from the pre-Caesarian Roman style, it was used by the Merovingian Franks and was the official style in Venice until 1797. So for the Venetians, the new year will not begin for three months.

March 25: Annunciation Style – begins the year on March 25 of the previous year (stilus pisanus 2020) or on March 25 of the given year (stilus florentinus, mos anglicanus 2019). This was one of the most popular styles during the Middle Ages. In England, March 25, or Lady Day, still marked the beginning of the new year for a variety of purposes.

Although they used the Annunciation Style in Pisa, they started counting a year earlier than everyone else. In other words, the new year might begin on March 25 in both Pisa and Florence, but in Piza it already would be 2019, and would become 2020 in March, while in Florence it would still be 2018 until March 25, when it would become 2019.

Easter Style – Begins the year on the movable feast of Easter Sunday of the given year. Sometimes the year is too short, and other times too long. This year would run from Easter Sunday, April 21, 2019 to Holy Saturday, April 11, 2020. Because Easter can fall on a day somewhere between March 22 and April 25, there is a possibility a date could occur twice in one year. The two dates had to be distinguished by marking them “after Easter” and “before Easter.” This style was the most popular one in France.

September 1: Byzantine Style – extends from September 1 of the previous year (2018) to August 31 of the given year (2019), in accordance with the Byzantine use of dating from the creation of the world.

This style was used by areas influenced by Constantinople, particularly during early period. Since Justinian’s time it was the day taxes were due.

September 24: Indictio Bedana – extends from September 24 of the previous year (2018) to September 23 of the given year (2019). Introduced by England’s “Venerable” Bede during the late 8th century, it was never used in that country, although later it was widely used on the Continent, especially in Germany and by the Imperial chancellery. It uses a date near the fall equinox, rather than the spring equinox, for the beginning of the year.

December 25: Christmas Style – extends from December 25 of the previous year (2018) to December 24 of the given year (2019). This is the style most widely used in the Middle Ages. It is the style that held sway during Anglo-Saxon England’s era, as well as being the New Year of choice for parts of France and Spain for 200 years.

Completely confused? You’re not alone. Historian Reginald Poole gave the following example:

“If we suppose a traveler to set out from Venice on March 1, 1245, the first day of the Venetian year, he would find himself in 1244 when he reached Florence; and if after a short stay he went on to Pisa, the year 1246 would already have begun there. Continuing his journey westward, he would find himself again in 1245 when he entered Provence, and on arriving in France before Easter (April 21) he would be once more in 1244. This seems a bewildering tangle of dates.”

The easiest way to determine how your persona would have dated the year is to use the online Calendar Utility created and maintained by Dr. Otfried Lieberknecht at: http://www.lieberknecht.de/~prg/calendar.htm. This is an amazingly useful tool. You can type in a Roman-style date and find out what its modern-style calendar date is. You can plug in any date and see what its official Roman calendar date is, along with what year it would be. For example, today is ii Kalendas (or Primus Kalendas) Januarius (the day before the Kalends of January) 2018 for me, because my persona is 12th century English. My new year is nearly four months away.

For those with non-Christian or early period personas, the task of identifying New Year’s Day can be challenging. In non-Christian parts of Europe, such as Scandinavia, parts of Germany and eastern Europe, local pagan customs prevailed. Most celebrated the new year sometime in March, usually tied to a spring fertility festival, although customs vary widely.

For those with Muslim personas or with personas that lived in Islamic-ruled areas of Spain or Sicily, tying the Muslim New Year to a Christian calendar date can be a challenge. Because the Muslims use a strictly lunar calendar, the Islamic year is only 354 days long. The Islamic new year begins eleven days earlier each year. It changes months and seasons regularly. Perhaps someone with a Muslim persona knows of a similar calendar utility to figure out historical dates. If so, please share.

And while Jewish personas would, of course, celebrate Rosh Hashanah in September, they most likely would keep secular records the same way others in their area did.

So to all of you, Happy New Year – sometime this year.

Queen’s Prize Tournament Court Summary, September 15, A.S. 53

In evening court:

Rowan of Golden Sea – Queen’s Chalice

Piers Fauconer – Torse

Skinna-Hrefna – AoA

Tessie of Cúm an Iolair – Leather Mallet

Knorr bestingr – AoA

Ki no Kotori – Calon Lily

Ashland de Mumford – Calon Lily

Other court tidings:

1 newcomer received a mug.

Lord Finán mac Crimthainn and Lady Gianna Viviani shared the Judges’ Choice award.

Emma Under Foot received the Youth Queen’s Prize.

Lord Hugo van Harlo received the Queen’s Prize.

A boon was begged for Marie le Faivre to join the Order of the Laurel.

Unknown Artist. Minstrels with a Rebec & a Lute.

13th c. Manasseh Codex. El Escorial, Madrid. Public domain in the US

Kingdom Arts & Sciences Event Court Summary, April 21, A.S. 52

In evening court:

Bjólfr Gunnvaldsson – AoA

Rosaline Fortescue – AoA

Anne von Husbergen – AoA

Tessie of Cum An Iolair – AoA

Alianora Jehannette des Amandiers – Laurel

Other court tidings:

3 newcomers received mugs.

The Youth Entrants present in court received wooden boxes (hope chests).

HL Roxelana Bramante won the Judges’ Choice award.

Lady Elaisse de Garrigues is the new Kingdom A&S Champion.

Mistress Aidan Cocrinn swore fealty as the new Kingdom Minister of Arts & Sciences.

Honorable Lady Vǫlu-Ingibiǫrg, Lady Dulcibella de Chateaurien, and Lady Fabia Narcissa Patricia were recognized for their nominations to the Blackfox Awards.

The Kingdom is in need of new boxes for the Crowns and Coronets. Questions should be directed to Mistress Rhianwen ferch Bran ap Gruffydd (Joan Steurer), the Regalia Coordinator. Email to regalia@calontir.org is one way to reach her.

Countess Elspeth of Stonehaven presented a gift of embroidery to Her Majesty.

Unknown Artist. Minstrels with a Rebec & a Lute.

13th c. Manasseh Codex. El Escorial, Madrid. Public domain in the US

From Their Royal Majesties: Bids for Boxes for Crowns and Coronets

Unto the Populace of Calontir, Greetings!

Unto the Populace of Calontir, Greetings!

The Kingdom is in need of new boxes for the Crowns and Coronets. The Crown currently has three sets of frequently-used Crowns, and the Heirs have two. Therefore, a total of 5 sets (10 boxes) are needed.

Anyone interested in making one or more sets of boxes is encouraged to submit a bid.

Your bid should include the following information:

-Design drawing, along with a description of how your boxes will meet the needs described below

-Budget

-Timeline

-(Optional, but encouraged): Photographs or other examples of similar work done by the bidder

Major qualities we are seeking for these boxes include:

-Protective: The major purpose of these boxes is to protect the Crowns during transport.

-Durable: The boxes must be able to withstand the rigors of years of packing and travel.

-Easily transportable: They should be stackable, packable, and easily carried.

Please base your bid on interior dimensions of approximately 6”x9”x11”. Successful bidders will be given access to take measurements of the set(s) of Crowns or Coronets for which they are making boxes.

Please submit your bid to the Their Royal Majesties at Falcon-Crown@calontir.org, Regalia Coordinator at regalia@calontir.org and copy the Kingdom Exchequer at Exchequer@calontir.org. Bids may also be submitted via post or hand-delivered.

Bids must be submitted by June 24th. Bids will be awarded by July 8th.

Questions should be directed to Rhianwen (Joan Steurer), the Regalia Coordinator.

In service to the Kingdom,

Rhianwen

Queen’s Prize Tournament court summaries, September 16, A.S. 52

Morning court:

Astriðr Birnudóttir – Torse

Dewi ap Gruffydd – AoA

Vǫlu-Dýrfinna Grímsdóttir – Golden Calon Swan

Felicia Maria Stanborough – Golden Calon Swan

Evening court:

Sean Angus MacDuinnchinn – Silver Hammer

Wolf – Queen’s Chalice

Gianna Viviani – Golden Calon Swan

Thorlein Knochenhauer – AoA

OddnæfR knarrarbringa – AoA

Ameline de Coity – Golden Calon Swan

Bragi Oddsson – Leather Mallet

Judith Champcenest – Golden Calon Swan

Batilda – AoA

Zarah bat Chesed – Golden Calon Swan

Maria Arosa de Santa Olalla – Calon Lily

Other court tidings:

Hugo van Harlo won the Judges’ Choice Award.

Konrad von Roth gave a gift of stained glass to Their Majesties.

8 newcomers received mugs.

Ameline de Coity presented a blank border scroll for Their Majesties’ use.

A boon was begged for Giraude Benet to join the Order of the Laurel.

Her Majesty awarded the Queen’s Prize (youth) to Sherbert Herrickson.

Her Majesty awarded the Queen’s Prize (adult) to Ysabel de la Oya.

Detail from the Hunterian Psalter, Glasgow University Library MS Hunter 229 (U.3.2) circa 1170. Public domain in the US

Kingdom Arts & Sciences Event Court Summary, April 15, A.S. 51

In evening court:

Hugo van Harlo – Leather Mallet

Amon Attwood – Leather Mallet

Elspeth of Stonehaven – Calon Lily

Vashti al-Asar – Leather Mallet

Elaisse de Garrigues – Golden Calon Swan

Abbatissa inghean lohne mhic Cuaig – Leather Mallet

Æsa á Norðrlonda – AoA

Beatrix Bogenschutz – Leather Mallet

Cera in Fheda – Silver Hammer

Zaneta Baseggio – Leather Mallet

Kainen Brynjólfsson – Queen’s Chalice

Zarah bat Chesed – Leather Mallet

Ysabel de la Oya – Leather Mallet

Tarique ibn Akmel el Ghazi – Silver Hammer

Leilia Corsini – Leather Mallet

Khuden Volkov – Torse

Other court news:

Hugo van Harlo won the Judges’ Choice award.

Viga-Valr viligísl (Vels) is the new Kingdom A&S Champion.

3 newcomers received mugs.

Ms. Katrei Grunenberg received her Laurel scroll, due since the reign of Valens III and Susannah II.

Unknown Artist. Minstrels with a Rebec & a Lute.

13th c. Manasseh Codex. El Escorial, Madrid. Public domain in the US

Happy New Year!

An article on time in Period by HL Lorraine Devereaux

March 25 is New Year’s Day for my persona, and for anyone who lived in Norman England during most of SCA period. March 25 also is the new year for those living in Pisa, Florence, Flanders, Brabant, Treves, Luxemburg, Lotharingia, most of France before 1100, the Papal court for a few centuries, and in Spain before 1350.

Often called Lady Day, March 25 was the Feast of the Annunciation (Feast of the Incarnation), traditionally held to be the day the angel Gabriel told the Virgin Mary she would be the mother of Jesus.

Although the Norman English still celebrated January 1 as the start of the year (as part of the Yule celebration), the actual New Year for legal and political purposes began on March 25 starting in 1155 and continuing until the reform of the English calendar in the 18th century. It was the day annual rents were paid, and later, taxes.

March 25 was a good day to start the year because originally it was the spring equinox. This was during Caesar’s time, before errors in the calendar caused the dates of the equinoxes and solstices to change. Many cultures began the year at or around the spring equinox or the winter solstice. (A few notably began the year near the autumn equinox, such as the Egyptians and Babylonians. The Jewish calendar is similar to the Babylonian calendar.)

By the 4th century, when Constantine called for reform of the Christian calendar, the spring equinox fell on March 21. Rather than take the extra four days out of the calendar, the church fathers chose to move the official equinoxes and solstices to their new dates. By then the quarter days were tied to religious holidays, and the new year did not change with the calendar.

But what about SCA folk whose personas come from other places and other times?

If your persona comes from Christian Constantinople, or from Naples and Sicily (from the 11th century on), the new year starts on September 1. That is the date the Byzantines believe the world began.

Starting in 1100 the French began the new year on Easter. Of course the problem with that is some years are longer than others. This year, from Easter 2016 to Easter 2017, the year is 20 days longer than normal. That means that if you want to record the date April 2, for example, you have to record it as April 2, 2016 (first) or April 2, 2016 (final). Last year (2015 to 2016) was nine days too short. Despite the obvious problems with this system, the French will used it until 1563.

In England before the mid-12 century, and in Ireland and Scotland during the early Middle Ages, the new year began on either December 25 or March 25, but most often on December 25. That would be the evening of December 24, since the Britons and Anglo Saxons began the day at dusk. Later, Ireland and Scotland switched to March 25.

Italy is a hodge-podge of dating conventions. The Venetians begin the new year on March 1, the date used by the early Romans (before Caesar’s calendar reform) and Merovingian Franks. In the Papal court before the 10th century they used the Byzantine’s September 1 for the new year. After that they switch to March 25.

In Florence and Pisa the new year began on March 25. However in Pisa people began their anno domini dating from Jesus’s conception, not his birth. So if 2017 begins today in Florence, 2018 begins today in Pisa.

The Germans are just as divided. Before 1200 most Germans celebrated New Year’s Day on December 25, but for a brief period the Holy Roman Emperors used September 24, a date promoted by the English scholar the “Venerable” Bede (yet never used in his home country).

During the 13th century the Germans for the most part use March 25. But during the 14th and 15th centuries many parts of what will be Germany switch back to December 25. The exceptions are Treves, Luxemburg and Lotharingia. They stay with March 25.

Flanders and Brabrant also stay with March 25, except during some scattered periods when they use Easter like their neighbors in France. During the latter half of the 16th century many Germans adopt January 1 as their New Year’s Day.

The Spanish use March 25 for the most part, until around 1350, when they switch to December 25 for a couple of centuries. Beginning in 1556 the Spanish adopt January 1 as the date of the new year.

If your area of Europe wasn’t covered, most likely your persona celebrated New Year’s Day on December 25 or March 25. Some Eastern European countries, as well as Persia, parts of India and parts of central and southern Asia, celebrate the new year on or near the spring equinox.

And of course after 1582, when Pope Gregory reforms the calendar, most of Catholic Europe switches to January 1, the date Caesar chose nearly 16 centuries earlier. By the end of SCA period all of Catholic Europe and even a few Protestant countries switch to January 1. The English (including the American colonies) won’t make the change until 1752. Turkey, Greece and Russia finally adopt the Gregorian calendar in the early 20th century.

The Met Museum Releases 375,000 More Images for Free

Under their Open Access program, The Met Museum has released 375,000 new images under the Creative Commons Zero (Public Domain) license, raising their library of freely available images to nearly half a million.

The collection is available and searchable at http://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection

You must be logged in to post a comment.